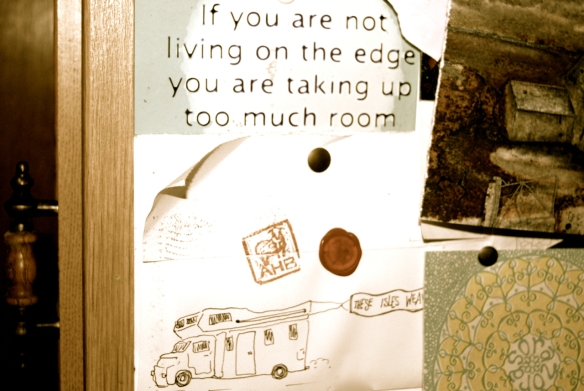

As I opted out of tenanthood and employeeship and moved my weaving business into a motorhome to take to the road on a shoestring in 2015, a dear family friend, who knows me very well, sent me the postcard pictured below.

Powerful, isn’t it? And tensely ambivalent? On the one hand a proud, wild, free, low impact, low consumption life of resilience on the margins; on the other, guilt and judgment of any comfort, luxury, security, safety or anything else that could be considered a privilege. Underpinned by the universal human need for AND RIGHT to some of all of the above. And fraught by the inevitable tension between the magnetic poles.

Moving one’s weaving workshop around these isles in a motorhome was one thing. Moving one’s weaving workshop in and out of a motorhome around these isles is quite another.

2019 has been a disruptive year. I tried to move to Brittany for the better quality of life it offers on a low income, but Murphy, my amazing familiar, died suddenly the week before. I moved into my planned accommodation regardless, but immediately had to move out again for health reasons. (I’m electrosensitive and the mobile phone mast 3km away took just three days to make me horribly ill because my flat was in direct line of sight.) My motorhome, leaking, mouldering and harbouring images of Murph’s dramatic death and empty bed, was no longer a home.

But the homelessness of the (relatively) privileged is very different from some people’s homelessness: since March I’ve stayed in three beautiful houses, and whilst moving all my worldly possessions and work from pillar to post has taken its toll on my health and productivity, there has been some positive impact on creativity.

Setting up house when I thought I’d be there a while, I made the effort to create a beautiful living and working space: a positive distraction from the greatest bereavement I’d ever suffered – for anyone who’s known the true and steady love of a loyal hound as their only companion will know that few other loves rival it. There was a sorrowfully empty corner by the woodburner where I’d planned for Murph to live, and the proximity of the beautiful woodland that he’d have enjoyed twice daily also taunted me cruelly. But neighbours were kind, friends were warm, the town was inspiring, and I created a lovely home. Rugs I’d woven looked (ahem) stunning on the pale floor complementing traditional Breton furniture unwanted by others and going for a song.

In anticipation of a larger home/workspace, though quite by chance, I’d seized upon a sought-after Dryad rug loom that I planned to install now my micro-business could expand a little. However, I had to change direction. Again. And fast. Again.

Never able to be off work for long (as craftspeople, artspeople and the self-employed well know), I packed what equipment I could into my old estate car and fled the Breton flat for a borrowed cottage. I hoped that just a brief retreat would bring me recovery, and so did not take my larger kit of loom and 100kg yarn stash. Instead I took the spinning wheel given me by my best friend for Christmas some years ago, and after a little input from another friend, hurriedly taught myself to spin.

At the time of buying the Dryad loom in Wales last year, the farmer had also sold me several kilos of fleece that his beautiful late wife had had prepared in Cornwall for the craft business she was shaping to replace her high-stress job. Life had other plans for her, alas. The fleece was beautiful too: lofty, lustrous Leicester Longwool from their own flock of ‘black’ silver sheep. I’d known that this, like the loom, was worth seizing when offered for sale on that serendipitous occasion, for both the quality and the tragic love story behind it.

So in the spring sunshine I foraged in hedgerows and meadows and neighbours’ gardens and in the kitchen and barn for dyestuffs, mordants and modifiers to bring natural colour to my spinning. Murphy was sorely missed every moment and my foraging walks were curtailed by dogless nervousness, but I consoled myself with the thought that foraging was a more perfect thing than ever to be paid to spend my time doing. (Not that my business brought in any money in late spring, the ‘hunger patch’, which lasts for months.)

I competed with the birds for ivy berries (they stripped the bushes while I took care not to) and with the bees for dandelions (I left them the most pollenous heads). I picked ivy leaves wantonly, and gorse flowers laboriously, and japonica flowers hopefully, and birch twigs furtively, and fallen camellias michievously. I was offered frosted azaleas, sent some biscuit tin mordant, and given some copper pipe. I found rusty nails, and, living without electricity because my tolerance had got so low, had an abundance of aluminium nightlight holders which I also used to mordant. (I even had friends to stay who, lightless at night with all electrics off, peed in a potty and donated to the cause. Ammonia is a known alkaliser for modifying natural dye colours, used traditionally in Hebridean tweed and everywhere else, and so I used it. Is that too much information?)

Instead of resting after huge upheaval and physical breakdown, I was as driven as a mad professor working sixteen hours a day seven days a week, leaping out of bed in the mornings to check my dye vats, stirring pots and pans on the stove, making copious notes, photo-documenting on my Instagram, filling endless buckets of water, whirling wet skeins around my head, burning my skin with caustic soda, provoking the occasional explosion, dropping bowls of boiling water between the stove and my dye station outside, and charging out of the house screaming like a fishwife at the birds for plucking fluff out of my drying yarn for their nests (I ended up donating a skein or two to their cause).

The outcome was five kilos of low impact art yarn, in (rare and exciting and not always fugitive) blues, mauves, pinks, greys, browns, rusts, yellows and greens. Some were dip dyed, and these are the most exciting to ply, knit or weave, as the end result is unpredictable and variegated across the finished project. Once plied, I felt that I’d taken the fleece to the most beautiful state that I could, and that the final step should be somebody else’s to take. And so I offer this range for sale especially for knitters.

I then had to vacate this lovely cottage, and, the flat investigated for electro-magnetic fields and deemed a write-off for me, moved to an equally lovely farmhouse elsewhere, thanks to some dear friends. (My middle class, privileged homelessness again: I used to work in Higher Education with her; he got me into these stalwart old Mercs.) This was a huge, woodfired, haunted, isolated, gingerbread house in unfamiliar, agricultural countryside. I felt very alone, especially when my car broke down, passers-by declined to jump start me and I thought I’d have to leave it in a layby until… what? But then friendlier neighbours familiar with old cars and undaunted by the two-minute and very simple manouevre helped out, deduced who I was, and then kept an unintrusive eye on me thereafter. (I’ve bought more bottles of wine as thanks for kindly neighbours and strangers than I’ve drunk myself.)

I then spent a very quiet, meditative period, unwell at times but largely in a gentle weaving rhythm, producing several grand’s worth of stock, going to bed with the sundown and watching the moon rise over the red tin roof of the barn through my open bedroom window at night.

Of course you’re never alone. During that peaceful time I had the most magical companionship: two kestrels were raising two young in the eaves of the gingerbread house. It was my fortune to be there at fledging time, and I watched the young, one male, one female, tumble and fall and stretch and jump and then fly. I witnessed them stooping submissively as they were dive-bombed by the swallows nesting in the barn, and hopping and squeaking as they were stalked by the cat, whose cover of undergrowth I cleared. Hopefully I was a help, and at close quarters they swivelled their heads and set their huge eyes upon me even in my bedroom. One evening I slurped up spaghetti on the patio while just ten yards away beneath the oak they slurped up entrails on the woodpile. Daily at dawn I saw their first landing and watched them assess the new day as they woke me with the sound of their claws on the red tin roof of the barn through my open bedroom window in the morning.

I was quiet. I read books about islands and their non-capitalist communities. I wove snugs and shawls as winter stock, and weaving a little of my ownspun Leicester Longwool was joyous, but never more joyous than weaving my ownspun Leicester Longwool dyed in kestrel colours.

So that was the spring and summer. Autumn brings autumn colours and selling season, and more househunting, and political activism. I’m in a warm, dry room in a different, lovely house in Devon, my semi-derelict van outside with the loom set up on a treadle and my workbenches still packed in my car and a question mark over my health and my next chapter. I was not in a position to catch the seasonal wave for the winter frenzy this year, but unless I find another way to stay afloat, I guess I’ll carry on weaving these isles nonetheless.

Buddleia, like nettle, is another one overlooked: a lurker in decaying industrial landscapes, abandoned dwellings and railway sidings; a post-apocalyptic pioneer; resistant; home always to a million butterflies. (Vive la revolution!)

Buddleia, like nettle, is another one overlooked: a lurker in decaying industrial landscapes, abandoned dwellings and railway sidings; a post-apocalyptic pioneer; resistant; home always to a million butterflies. (Vive la revolution!)